Spelling Sensitivity in Russian Speakers Develops by Early Adolescence

Scientists at the RAS Institute of Higher Nervous Activity and Neurophysiology and HSE University have uncovered how the foundations of literacy develop in the brain. To achieve this, they compared error recognition processes across three age groups: children aged 8 to 10, early adolescents aged 11 to 14, and adults. The experiment revealed that a child's sensitivity to spelling errors first emerges in primary school and continues to develop well into the teenage years, at least until age 14. Before that age, children are less adept at recognising misspelled words compared to older teenagers and adults. The study findings have been published in Scientific Reports.

By the time they finish primary school, children's reading of high-frequency words becomes automated. Behavioural studies measuring parameters like reaction time and error rates show that children at this age can reliably distinguish between words and letter strings resembling words.

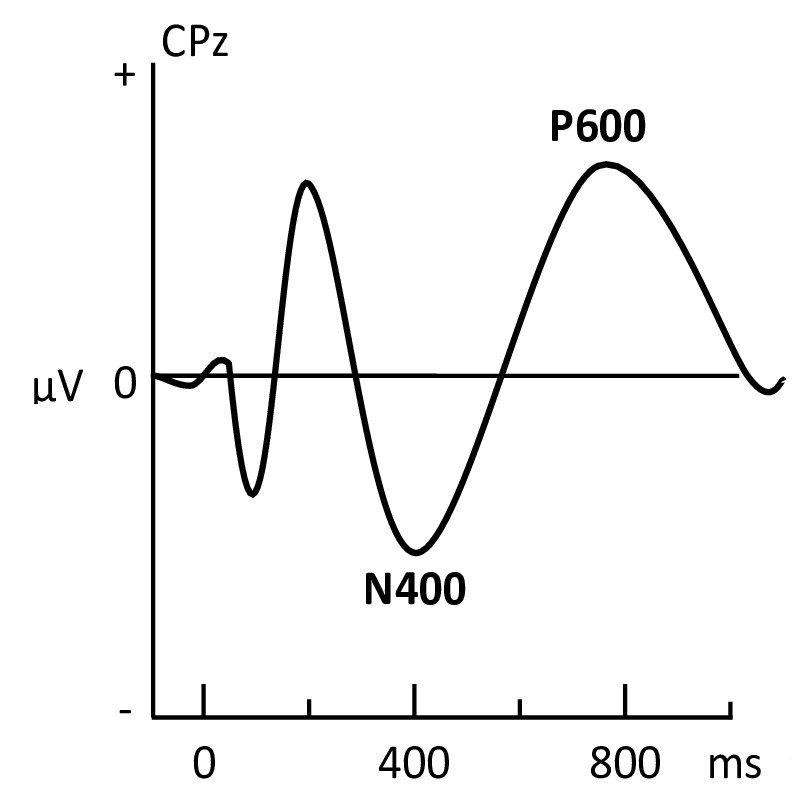

The event-related potential (ERP) method is a promising approach to examining the reading process in neurophysiological research. Event-related potentials are the brain's electrophysiological responses to perceptual events (such as specific sensations), cognitive events (like decision-making), or motor events (such as pressing a button).

The ERP method allows for assessing the brain's response to verbal stimuli and identifying time intervals—components within the ERP—associated with their processing. In primary school-age children, the ERPs in response to words and strings of non-letter symbols differ at 200 ms after presentation, but distinctions between words and meaningless strings of actual letters are detected much later, only after 400 ms. This indicates that such stimuli are more challenging for young children to process.

However, sensitivity to spelling patterns is not limited to the ability to distinguish words from meaningless letter sequences but also involves more complex skills related to recognizing spelling errors. The issue is that the neural bases underlying the development of orthographic sensitivity remain poorly understood.

Scientists at the RAS Institute of Higher Nervous Activity and Neurophysiology and the Centre for Cognition and Decision Making of the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience used electroencephalography (EEG) to investigate event-related potentials associated with spelling error recognition. The study involved children aged 8 to 10, early adolescents aged 11 to 14, and adults aged 18 to 39, all of them native speakers of Russian. None of the subjects experienced spelling difficulties.

The subjects were presented with words on a screen, some of which were spelled correctly while others were misspelled. The task was to determine whether the word on the screen was spelled correctly.

The experiment showed that all the groups successfully identified both correctly spelled and misspelled words. The average error rate, even among children aged 8 to 10, did not exceed 14%, although children had more incorrect answers and longer reaction times compared to early adolescents and adults.

Early adolescents and adults showed similar, though not identical, behavioural results. The response time to both types of stimuli and the percentage of erroneous responses to correctly spelled words did not differ between these groups. However, early adolescents were worse than adults at recognising misspelled words.

In adult participants, differences in ERPs between correctly and incorrectly spelled words were observed in two distinct time windows. This indicates that the recognition of spelling correctness by adults involves two ERP components: an early component around 400 ms and a later one of up to 600 ms, probably related to re-checking the spelling for errors.

In children aged 8 to 10, there were no differences in ERPs between correctly spelled and misspelled words. According to the researchers, this suggests that the ability to quickly recognise correct spelling is just beginning to develop at this age. Interestingly, in early adolescents, spelling recognition was reflected only at the later stage corresponding to the 600 ms component, ie they did not exhibit early differences related to automated spelling recognition.

The experiment revealed that a child's orthographic sensitivity first emerges in primary school and continues to develop well into the teenage years, at least until age 14. These findings contribute to our understanding of the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the mastery of Russian spelling and how these mechanisms evolve with age.

Leading Research Fellow, Centre for Cognition and Decision Making, Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience

In our study, adults and adolescents did not differ in their reaction times to any of the stimuli: both groups recognized correctly and incorrectly spelled words at similar speeds. This suggests that they likely employed similar reading and spelling recognition strategies. Nevertheless, the percentage of misidentified misspelled words was higher in early adolescents compared to adults, suggesting that spelling sensitivity is still developing at this age.

See also:

Scientists Discover Why Parents May Favour One Child Over Another

An international team that included Prof. Marina Butovskaya from HSE University studied how willing parents are to care for a child depending on the child’s resemblance to them. The researchers found that similarity to the mother or father affects the level of care provided by parents and grandparents differently. Moreover, this relationship varies across Russia, Brazil, and the United States, reflecting deep cultural differences in family structures in these countries. The study's findings have been published in Social Evolution & History.

When a Virus Steps on a Mine: Ancient Mechanism of Infected Cell Self-Destruction Discovered

When a virus enters a cell, it disrupts the cell’s normal functions. It was previously believed that the cell's protective response to the virus triggered cellular self-destruction. However, a study involving bioinformatics researchers at HSE University has revealed a different mechanism: the cell does not react to the virus itself but to its own transcripts, which become abnormally long. The study has been published in Nature.

Researchers Identify Link between Bilingualism and Cognitive Efficiency

An international team of researchers, including scholars from HSE University, has discovered that knowledge of a foreign language can improve memory performance and increase automaticity when solving complex tasks. The higher a person’s language proficiency, the stronger the effect. The results have been published in the journal Brain and Cognition.

Artificial Intelligence Transforms Employment in Russian Companies

Russian enterprises rank among the world’s top ten leaders in AI adoption. In 2023, nearly one-third of domestic companies reported using artificial intelligence. According to a new study by Larisa Smirnykh, Professor at the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences, the impact of digitalisation on employment is uneven: while the introduction of AI in small and large enterprises led to a reduction in the number of employees, in medium-sized companies, on the contrary, it contributed to job growth. The article has been published in Voprosy Ekonomiki.

Lost Signal: How Solar Activity Silenced Earth's Radiation

Researchers from HSE University and the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences analysed seven years of data from the ERG (Arase) satellite and, for the first time, provided a detailed description of a new type of radio emission from near-Earth space—the hectometric continuum, first discovered in 2017. The researchers found that this radiation appears a few hours after sunset and disappears one to three hours after sunrise. It was most frequently observed during the summer months and less often in spring and autumn. However, by mid-2022, when the Sun entered a phase of increased activity, the radiation had completely vanished—though the scientists believe the signal may reappear in the future. The study has been published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics.

‘Engagement in the Scientific Process’: HSE Launches Master’s Programme in Neurobiology

The HSE University Academic Council has elected to launch a new Master's programme in Neurobiology for students majoring in Biology. Students of the programme will have access to unique equipment and research groups, providing them with the knowledge and experience to pursue careers in science, medicine and pharmacy, IT and neurotechnology, and education and HR services.

Banking Crises Drive Biodiversity Loss

Economists from HSE University, MGIMO University, and Bocconi University have found that financial crises have a significant negative impact on biodiversity and the environment. This relationship appears to be bi-directional: as global biodiversity declines, the likelihood of new crises increases. The study examines the status of populations encompassing thousands of species worldwide over the past 50 years. The article has been published in Economics Letters, an international journal.

Scientists Discover That the Brain Responds to Others’ Actions as if They Were Its Own

When we watch someone move their finger, our brain doesn’t remain passive. Research conducted by scientists from HSE University and Lausanne University Hospital shows that observing movement activates the motor cortex as if we were performing the action ourselves—while simultaneously ‘silencing’ unnecessary muscles. The findings were published in Scientific Reports.

Russian Scientists Investigate Age-Related Differences in Brain Damage Volume Following Childhood Stroke

A team of Russian scientists and clinicians, including Sofya Kulikova from HSE University in Perm, compared the extent and characteristics of brain damage in children who experienced a stroke either within the first four weeks of life or before the age of two. The researchers found that the younger the child, the more extensive the brain damage—particularly in the frontal and parietal lobes, which are responsible for movement, language, and thinking. The study, published in Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology, provides insights into how age can influence the nature and extent of brain lesions and lays the groundwork for developing personalised rehabilitation programmes for children who experience a stroke early in life.

Scientists Test Asymmetry Between Matter and Antimatter

An international team, including scientists from HSE University, has collected and analysed data from dozens of experiments on charm mixing—the process in which an unstable charm meson oscillates between its particle and antiparticle states. These oscillations were observed only four times per thousand decays, fully consistent with the predictions of the Standard Model. This indicates that no signs of new physics have yet been detected in these processes, and if unknown particles do exist, they are likely too heavy to be observed with current equipment. The paper has been published in Physical Review D.