Scientists Reveal Cognitive Mechanisms Involved in Bipolar Disorder

An international team of researchers including scientists from HSE University has experimentally demonstrated that individuals with bipolar disorder tend to perceive the world as more volatile than it actually is, which often leads them to make irrational decisions. The scientists suggest that their findings could lead to the development of more accurate methods for diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder in the future. The article has been published in Translational Psychiatry.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic affective condition characterised by alternating episodes of extreme elation (mania) and severe depression. According to the WHO, an estimated 40 million people worldwide live with bipolar disorder, but diagnosing the condition can be challenging, as its symptoms are not always apparent.

Studies show that individuals with bipolar disorder, even during remission, exhibit specific behavioural and brain activity patterns that may indicate the condition. In particular, patients with bipolar disorder have been found to exhibit impairments in their decision-making processes. Normally, when making a decision, a person tries to choose the option that offers the greatest reward. If the choice proves to be correct, they are likely to make the same decision again next time. However, circumstances can change, requiring a person to reassess which option offers the greatest benefit. Patients with BD often struggle to recognise when it is necessary to adjust their decision-making strategy.

A group of researchers from HSE University, Sechenov University, the Max Planck Institute, and Goldsmiths, University of London, conducted an experiment to investigate how individuals with bipolar disorder adapt to environmental changes and make decisions.

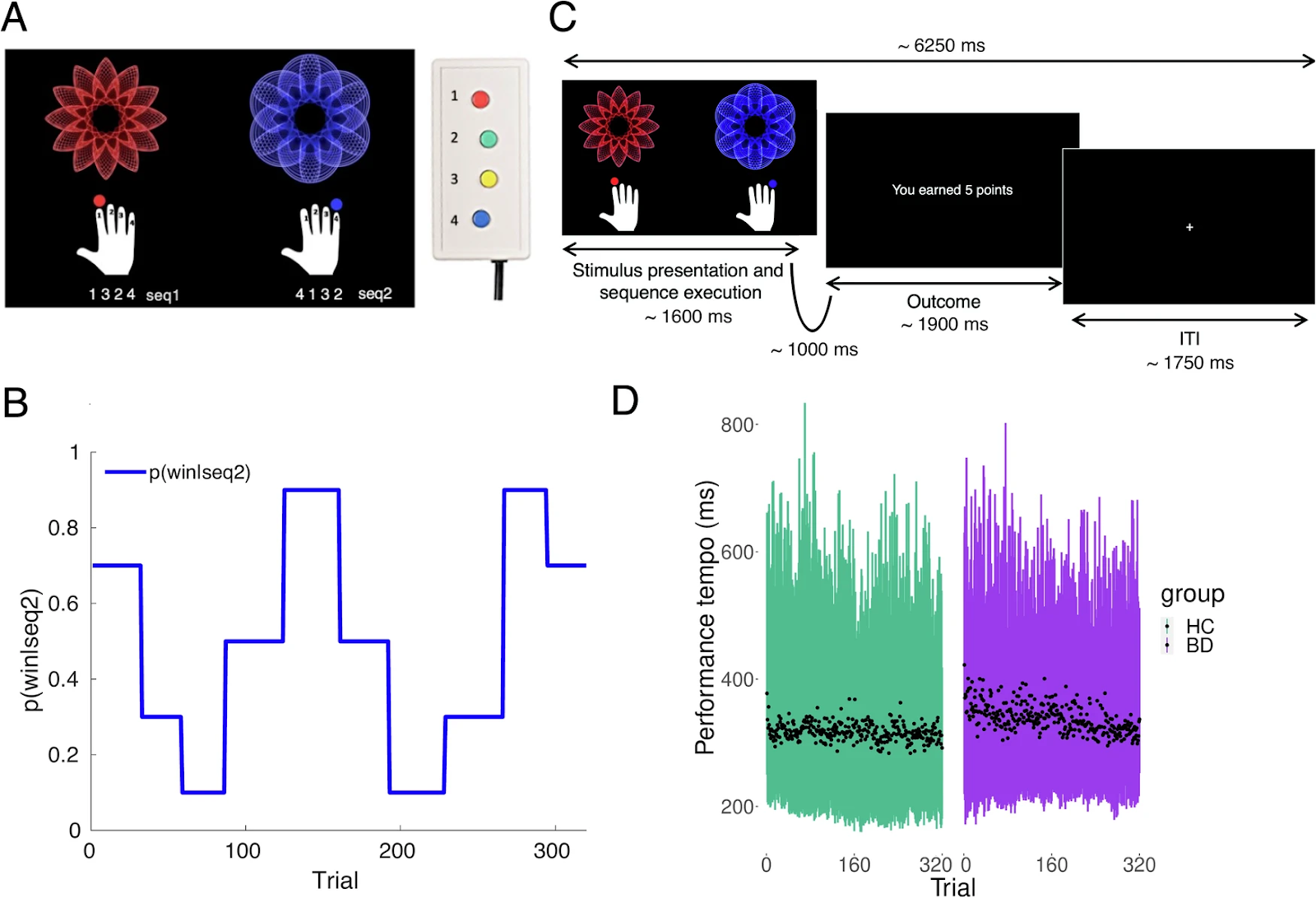

The study included 22 bipolar patients in remission and 27 healthy volunteers who served as the control group. Participants were instructed to earn as many points as possible by selecting either a blue or red image on a computer screen. Each option had a certain probability of winning, which changed throughout the experiment. For example, initially the blue image won 70% of the time, but later its winning probability dropped to 30%. Throughout the experiment, participants’ neuronal brain activity was monitored using magnetoencephalography (MEG).

Marina Ivanova

'This experimental design mimics real-world conditions, which are also full of uncertainties and require constant decision-making—even in everyday situations. For example: should you pet a cat, or is it better not to? Will it purr or scratch? We try to anticipate the consequences of our choices and make the best decision accordingly,' explains Marina Ivanova, Junior Research Fellow at the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience and primary author of the study.

The results of the experiment showed that participants with bipolar disorder perceived the environment as more volatile than it actually was, which often led them to make incorrect choices.

'If a person makes a decision and it turns out to be the right one, they will likely repeat that choice next time. However, someone with bipolar disorder may change their strategy even after a successful outcome,' says Ivanova.

The scientists also observed neural differences in brain regions involved in decision-making, specifically the medial prefrontal, orbitofrontal, and anterior cingulate cortices. At the neural level, while healthy individuals exhibited alpha-beta suppression and increased gamma activity during the experiment, participants with bipolar disorder showed dampened effects.

'Our study reveals that even outside of manic or depressive episodes, people with bipolar disorder process information about environmental changes differently. They constantly anticipate changes but struggle to properly learn from them when they occur. As a result, their decisions are more spontaneous and unpredictable than those of the control group,' comments Ivanova. ‘However, it is important to remember that our experiment only simulates real life, so we should be cautious when applying these findings to actual everyday situations.'

The results may be useful for developing models to diagnose bipolar disorder and predict its recurrence. In the future, this approach could be adapted to other mental health conditions involving adaptive learning impairments and may also serve as an important step toward advancing computational psychiatry.

See also:

HSE Researchers Offer Guidance to Prevent Undergraduate Burnout

Researchers at the HSE Institute of Education have identified how much time students should ideally devote to their studies, extracurricular activities, and personal life to maintain strong academic performance without compromising their mental health. An analysis of responses from 2,753 students, combined with their actual academic results, revealed several risk factors—such as excessive homework—as well as positive factors, including sufficient sleep, regular exercise, and moderate participation in projects. Based on these findings, the researchers developed practical recommendations for both students and universities. The paper has been published in the European Journal of Education.

Scientists Discover Why Parents May Favour One Child Over Another

An international team that included Prof. Marina Butovskaya from HSE University studied how willing parents are to care for a child depending on the child’s resemblance to them. The researchers found that similarity to the mother or father affects the level of care provided by parents and grandparents differently. Moreover, this relationship varies across Russia, Brazil, and the United States, reflecting deep cultural differences in family structures in these countries. The study's findings have been published in Social Evolution & History.

When a Virus Steps on a Mine: Ancient Mechanism of Infected Cell Self-Destruction Discovered

When a virus enters a cell, it disrupts the cell’s normal functions. It was previously believed that the cell's protective response to the virus triggered cellular self-destruction. However, a study involving bioinformatics researchers at HSE University has revealed a different mechanism: the cell does not react to the virus itself but to its own transcripts, which become abnormally long. The study has been published in Nature.

Researchers Identify Link between Bilingualism and Cognitive Efficiency

An international team of researchers, including scholars from HSE University, has discovered that knowledge of a foreign language can improve memory performance and increase automaticity when solving complex tasks. The higher a person’s language proficiency, the stronger the effect. The results have been published in the journal Brain and Cognition.

Artificial Intelligence Transforms Employment in Russian Companies

Russian enterprises rank among the world’s top ten leaders in AI adoption. In 2023, nearly one-third of domestic companies reported using artificial intelligence. According to a new study by Larisa Smirnykh, Professor at the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences, the impact of digitalisation on employment is uneven: while the introduction of AI in small and large enterprises led to a reduction in the number of employees, in medium-sized companies, on the contrary, it contributed to job growth. The article has been published in Voprosy Ekonomiki.

Lost Signal: How Solar Activity Silenced Earth's Radiation

Researchers from HSE University and the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences analysed seven years of data from the ERG (Arase) satellite and, for the first time, provided a detailed description of a new type of radio emission from near-Earth space—the hectometric continuum, first discovered in 2017. The researchers found that this radiation appears a few hours after sunset and disappears one to three hours after sunrise. It was most frequently observed during the summer months and less often in spring and autumn. However, by mid-2022, when the Sun entered a phase of increased activity, the radiation had completely vanished—though the scientists believe the signal may reappear in the future. The study has been published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics.

Banking Crises Drive Biodiversity Loss

Economists from HSE University, MGIMO University, and Bocconi University have found that financial crises have a significant negative impact on biodiversity and the environment. This relationship appears to be bi-directional: as global biodiversity declines, the likelihood of new crises increases. The study examines the status of populations encompassing thousands of species worldwide over the past 50 years. The article has been published in Economics Letters, an international journal.

Scientists Discover That the Brain Responds to Others’ Actions as if They Were Its Own

When we watch someone move their finger, our brain doesn’t remain passive. Research conducted by scientists from HSE University and Lausanne University Hospital shows that observing movement activates the motor cortex as if we were performing the action ourselves—while simultaneously ‘silencing’ unnecessary muscles. The findings were published in Scientific Reports.

Russian Scientists Investigate Age-Related Differences in Brain Damage Volume Following Childhood Stroke

A team of Russian scientists and clinicians, including Sofya Kulikova from HSE University in Perm, compared the extent and characteristics of brain damage in children who experienced a stroke either within the first four weeks of life or before the age of two. The researchers found that the younger the child, the more extensive the brain damage—particularly in the frontal and parietal lobes, which are responsible for movement, language, and thinking. The study, published in Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology, provides insights into how age can influence the nature and extent of brain lesions and lays the groundwork for developing personalised rehabilitation programmes for children who experience a stroke early in life.

Scientists Test Asymmetry Between Matter and Antimatter

An international team, including scientists from HSE University, has collected and analysed data from dozens of experiments on charm mixing—the process in which an unstable charm meson oscillates between its particle and antiparticle states. These oscillations were observed only four times per thousand decays, fully consistent with the predictions of the Standard Model. This indicates that no signs of new physics have yet been detected in these processes, and if unknown particles do exist, they are likely too heavy to be observed with current equipment. The paper has been published in Physical Review D.